The Artist in Exile

A journey through the modern machinery of ostracism, the personal collapse it caused, and the hard-won resolve that followed.

Editors Note: Below you will find a long-form essay by Mary McDonald-Lewis. We generally don’t publish long-form content on our Substack, but Mary’s voice and experience are so timely and important that we feel compelled to share this in its original form.

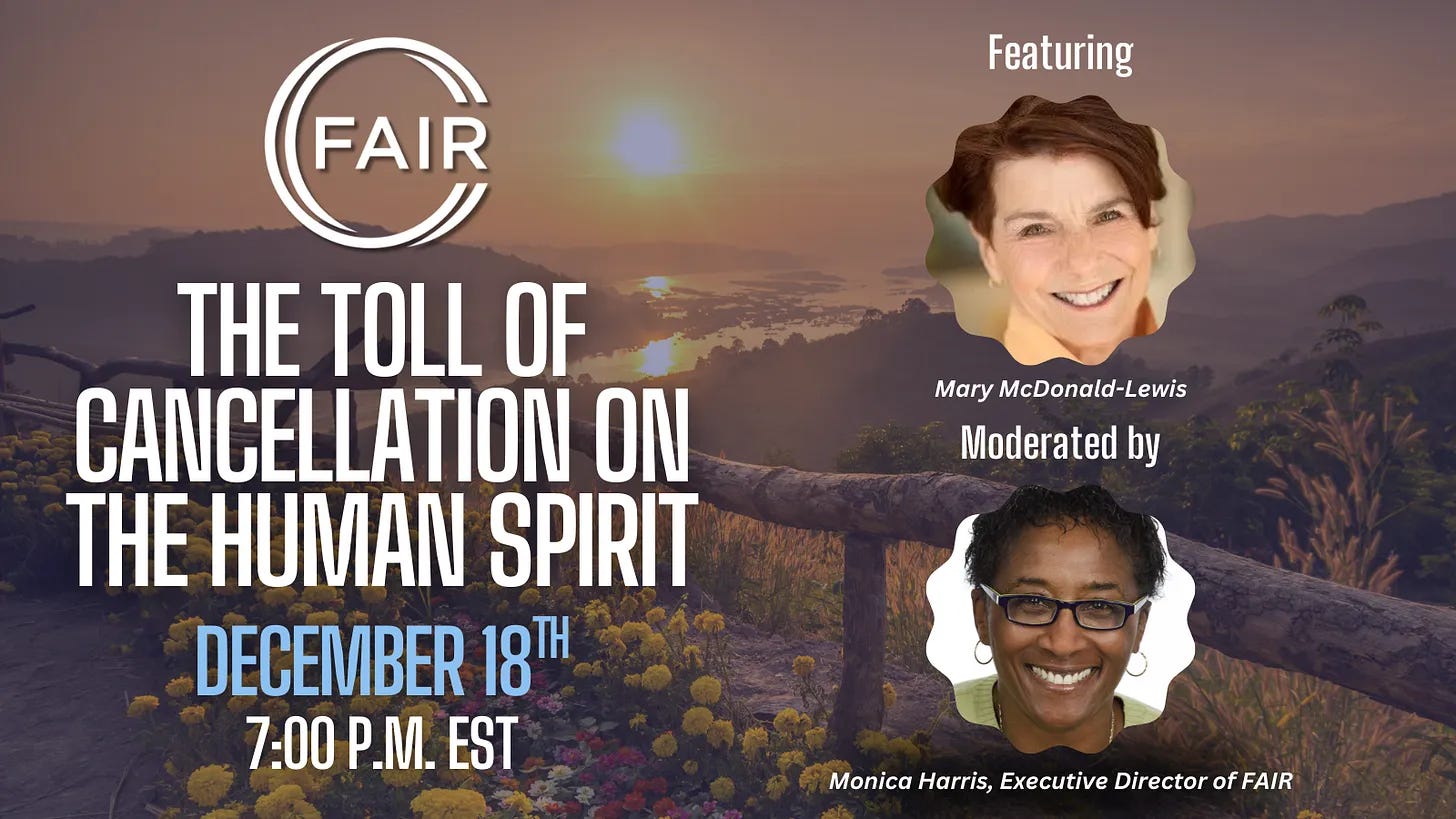

On December 18th at 7pm EST, Mary and Monica Harris will explore the human cost of cancellation, the spiritual and emotional dimensions that often go unseen, and the importance of building a culture where disagreement does not mean disposability. Mary will share her story, her losses, her resilience, and her hope for a better future. If Mary’s story moves you, please consider joining us.

It was a brisk September San Francisco morning, and the brunch joint was jumping. The moment had come. She had to know, in case what I feared was going to come to fruition. I pushed aside my maitake soft scramble, took a deep breath, and told my lovely daughter, as carefully as I could, that I had lost “purpose” in my life.

But what I meant was, I had lost the will to live. What I meant was, I was considering suicide.

How did I get here?

This is the third of three essays for FAIR, the first two of which track my initial cancellation in theater, and my subsequent cancellation and continued hounding. This one tells the story of my escape across the country... and my last cancellation. In the first, I ended up hoping to return to my art. The second concluded with the suspicion that my torment would continue, should I try to make art again.

It did. And it got me canceled for that third and final time.

So here is the only story I am permitted to tell now: my life sentence as an exiled artist, how it led to thoughts of suicide over eggs and cappuccino, and what happened after that brunch.

A little back story. After a dozen years as their resident dialect coach, in 2019 I was fired from both of Portland Oregon’s largest Equity theater companies for refusing to use demanded pronouns. Following this, from Oregon’s most popular coach I became the most reviled: dropped from every other theater in the state, stage work dried up entirely. But I was busy with film/television jobs and voice-over gigs, my union pensions and Social Security had kicked in, and theater never paid much anyway. Still, it was my local community, and most in it had begun to abandon their friendship with me, too. Cancellation #1.

About four years later, in 2023, I pitched a longtime friend and colleague on adapting Shakespeare’s Macbeth to a shorter, lens-down version—The Macbeths—which focused on the relationship between Mackers and Lady M. Other than the loss of work and friendships, it had been fairly quiet, especially with COVID-19 carving a firebreak through the, well, firestorms of the woke Portland theater community.

But as soon as the leftists discovered I was working on a new project, they attacked it by promoting me as a transphobe, racist, Zionist, and so on all over social media; by pushing my partner and the director to abandon me; by promising to destroy the reputations of anyone associated with the show; and by threatening pickets at the theater on opening night.

It worked.

My show was boycotted, I was betrayed by my partner and the director, kicked out of the theater space, damned in Willamette Week, Portland’s local left-wing rag, and attacked and threatened by the community.

The show shut down two weeks from opening, and I immediately made plans to move. Cancellation #2.

(Nota bene: See the end of the essay for more on The Macbeths.)

After 32 years in Portland, 70 days later I pulled up to my new home, 3,000 miles away in the Mid-Atlantic South. Once I was tucked into my cozy new neighborhood, an old writing partner living nearby reached out and proposed we start a readers theater company—that’s a staged reading operation where actors perform with script in hand, often simply at music stands. I’d had my own staged reading company for 20 seasons in Portland, and thought that was a splendid idea. So just as with The Macbeths, I got busy. I designed the logo, prepared the marketing, publicized auditions, met with the actors, began to solidify the cast, located a performance space... but when I let an interested actor know I only used standard pronouns on my stage, it happened all over again.

The actor leapt to various local theater pages on Facebook, declaring me a TERF (and a racist, for some reason), demanding the company be killed, and encouraging others to pile on—which they did by the dozens on those social media sites. They found the Willamette Week article about The Macbeths and published it widely on Facebook. They connected with the leftist actors in the Pacific Northwest and followed their playbook to the letter. Though inaccurate and hyperbolic in the extreme, Dustin K. Britt posted on several pages:

“Mary McDonald-Lewis has come to (my location). A known racist and TERF, she’s crisscrossing the country trying to get awful plays produced. She’s raised enough money to try and get readings here. It’s important that (the staged reading company) never become an entity in this community or any other.”

A typical reply was:

“It’s wild that she thought she could come to the Triangle and be successful with her disgusting views.”

This inspired Beau Clark’s suggestions:

“Everyone should post on all your own local pages tagging both (the company) and (the theater space). Let them see (this is from) the vast majority of the triangle theater community. Flood both of the ‘mentions’ sections with indicators that by aligning with Mary Mac, any patronage will equal being complicit in transphobia. Also, they have a staged reading on Oct 16th. Ready up some signs and flood the sidewalk outside.”

Britt and the mob went on to both condemn and pressure my partner to bail, and to threaten the theater space with boycott. Within days, I was blocked from all area theater social media pages, we lost the performing venue, the company folded, and the project was dead. It was chapter and verse the exact same cancellation plan as that which killed The Macbeths. Cancellation #3.

This was underscored soon after by an old-school, late-night obscene phone call wishing me all kinds of nasty harm, hoping, oddly, that both the president and I would die of “blood clots,” and by an encounter I had in a local dog park, where a man offered to introduce me to the storytelling community. I was thrilled and eagerly provided him my name and contact information. Within an hour he texted me: “Mary, I’ve done a bit of looking at social media and reading article published in Oregon. I’m sorry to say I don’t think you would care much for many of my views,” and he wished me luck. A dog park cancellation for dessert!

The bright spot was, my former partner remains my steadfast friend, though we are no longer producing together.

The dark spot was, I had finally learned the truth: after three vicious cancellations, it was clear that I was exiled forever from making art. And that’s what made me feel like there was no point in living any longer.

And there are very real reasons for this feeling.

We are born confused, with not much to go on other than cling to your mother and mimic everything you see (for better or for worse). We are also born with a need to tidy up that confusion, to recognize patterns and strive for harmony—that is, to somehow rhythm and rhyme the chaos outside, and inside, us. So we set out to organize our world in deeply personal ways. Grappling with the immensity of infinity, Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli expressed one facet of his organizing framework in Ars Conjectandi, written in the late 1600s, this way:

Even as the finite encloses an infinite series.

And in the unlimited limits appear,

So the soul of immensity dwells in minutia.

And in the narrowest limits no limit in here.

What joy to discern the minute in infinity!

The vast to perceive in the small, what divinity!

Rather than look outward, Benoît Mandelbrot’s search for harmony took him inward, to discover what became known as the Mandelbrot set, a system described by Quanta magazine’s math editor Jordana Cepelwicz in The Quest to Decode the Mandelbrot Set, Math’s Famed Fractal as “more than a fractal, and not just in a metaphorical sense. It serves as a sort of master catalog of dynamical systems—of all the different ways a point might move through space according to a simple rule.”

Like Vespucci at the edge of the Amazon, Mandelbrot sought to discover the mouth of the river, the font—something, anything—that organized the way a point—us—might move through space, hopefully according to a simple rule. From Pythagoras of Samos to Jackson Pollock of Cody, we are all searching for a Theory of Everything, and we describe it in the way our mind dictates, often through art. We struggle to compose the music of the spheres, we wrestle with words to write about the mystery and with numbers to decode it, and with molten metal to form our Thinker. Ecce homo. As the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling soars nearly 70 feet above us, Michelangelo’s God reaches to Adam, his hand outstretched, and Man is touched, created, born. Millions have sighed at its beauty, but below the immediate appreciation is the relief at the artist’s explanation: here we are, moving through space, accompanied.

Now take away Bernoulli’s pen, Mandelbrot’s microscope, Vespucci’s sails, Pythagoras’ voice, Pollock’s paintbrush, Rodin’s bronze, Michelangelo’s lapis lazuli. Banish them from their art. Two things have been accomplished: you have driven these men to madness, and you have deprived us of all that they gave us, and everything that came after it.

It is a nearly perfect crime, for two reasons. First, because the hand of the assassin is not seen—the figurative or actual death accomplished through the denial of essential personhood. Profound depression follows, and in the end, the artist conspires with their tormentors and does the silencing themselves. Second, because every time one artist is censored, canceled, fired, deplatformed, doxed, swatted, threatened with rape or murder, or actually harmed, most of the rest of the arts community either joins in the mob or doubles down on their silence. No perpetrator, no witnesses, no outrage, no justice. Simply the little loss of one artist, and the monumental loss of that artist’s voice.

Given that our articulated purpose, married, if we are lucky, to an abiding way of expressing it, approaches the sacred, then rendering it mute rises to that measure as well. It is a theft that is close to stealing the soul. But the canceled artist loses even more. After his work is taken from him, he loses his tribe: family, friends, colleagues turn their backs on him, and he is both silenced and utterly alone.

Shunning is a practice used in some churches and all cults, and cancellation is its modern sinister application. A recent Psychology Today article, How Religious Shunning Ruins Lives, details the damage: “Research has shown that shunned individuals often experience feelings of depression, helplessness, hopelessness, low self-esteem, suicidal ideation, and self-harming behaviors.”

Shunning—cancellation—according to Dr. Kipling D. Williams, professor of psychological sciences at Purdue University, “is like a social death penalty—and studies prove this point. Exclusion has been found to cause pain that cuts deeper and lasts longer than a physical injury.” The brain registers the rejection as a physical wound, with the distinct disadvantage that while bodily harm heals, brain harm is far more difficult to resolve. This is particularly true as shunning attacks four basic human needs: belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence. What follows is hopelessness, loss of health, home, and possibly life. Shunning is malevolent violence of the cruel and unusual kind.

Williams, author of Ostracism: The Power of Silence, expands on the research on this podcast.

The artist who has their organizing principle taken from them no longer has a means of creating and maintaining harmony. They face nothing but chaos, and they are shunned, left alone in this state. Is it any wonder that abandonment in this dark and howling landscape can lead to thoughts of self-destruction? From the same article: “Humans have a primal need for social support. Without a sense of belonging—a feeling of emotional safety and context—people come to fear that their very lives are at risk. They lose the ability to trust and connect with others, instead becoming consumed by the task of surviving alone.”

Once banished, the artist begins to manifest the trauma. Having lost both their coping mechanism and their community, they can feel isolated, lonely, and paranoid. For me, in Portland before I fled, those rare times I went to the theater I was nervous, awkward, not knowing who my friends or (as far as they were concerned) enemies were. It becomes hard to be one’s self, as we second-guess all interactions. The unreturned phone calls, texts, emails seem proof of yet another abandonment, whether true or not. And new friends feel impossible to make. Remember, Maslow places “love and belonging” in third place in his hierarchy of needs—between survival and safety, below, and esteem and self-actualization, above. This makes sense to me: connection is a kind of fulcrum, a psychological/emotional on-off switch which informs the other four.

And this brings me back to that table in the noisy bistro, considering suicide.

I was carved out by my final cancellation. Defeated. I used to say my motto was “Tell a story, save the world,” and now I was never going to tell a story again. I was this close to giving up. I confessed to my daughter, in so many words, that I didn’t want to live; I made my way back across the country, went inside, and closed the door.

But then I recalled the voice that spoke to me during my second cancellation, and which ended my second essay for FAIR. “I didn’t come here to have an easy time,” it told me. So, fending off the demon thoughts persecuting me, I did something I don’t usually do: I asked for help. I reached out to FAIR again, to write this essay to all of you. And from my conversation with Brent Morden, Director, FAIR in the Arts, came my salvation.

I told Brent I was lost—adrift in purpose, awash in hopelessness. I had no compass for a path forward, and my scripts, both figurative and literal, had been torn to pieces. “Time to improvise,” Brent said. “Have you ever read Albert Murray? He says improvisation is the hero’s journey.” I was instantly interested. Phone cradled to my ear, I hopped online and ordered his collected essays and memoirs immediately.

Murray (1916–2013) was a novelist, essayist, biographer, literary and music critic, and teacher. His passions were the blues, jazz, and literature, with a special love for Duke Ellington and his friend Ralph Ellison, and for Hemingway and Thomas Mann. He was also a thinker of colossal and prodigious status. The Hero and the Blues is his long essay on the subject Brent brought up.

Consider the jazz break, Murray says, as the moment the hero is called to improvise. Every other musician on that stage is silent, and it’s up to the sax player to make his case. He moves into the void, calling on everything inside him: the sweet and the sour, the lost and the found, the grief and the grace to make something new. Brand new, and brave, and healing, and an aid to everyone who hears it.

God touches Adam’s hand, and with an infant’s gasp, he comes to life. Improvising.

And it’s needed. Moving from the jazz man to the scribe, “It is the writer, as artist, not the social or political engineer, or even the philosopher, who first comes to realize when the time is out of joint. It is he who determines the extent and gravity of the current human predicament, who, in fact, discovers and describes the hidden elements of destruction, sounds the alarm, and even… designate the targets.”

There’s plenty in the way of this artistic improv, maybe more than ever before. But (agreeing with Aurelius here) Murray tells us the obstacle is the way. He calls it “antagonistic cooperation, a concept which is indispensable to any fundamental definition of heroic action, fiction or otherwise. The fire in the forging process, like the dragon which the hero must always encounter, is of its very nature antagonistic, but it is also cooperative at the same time. For all its violence, it does not destroy the metal which becomes the sword. It functions precisely to strengthen and prepare it to hold its battle edge, even as the all but withering firedrake prepares the questing hero for subsequent trials and adventures.”

To engage in the artist’s quest is Quixotic, to say the least, especially today. The leftist theater community on both coasts of this country stole my storytelling and imperiled my life. But since every day, as Murray told one interviewer, “is like either … cut your throat or be down at the Savoy [Ballroom] by 9:30,” I’m going to pick up my sword, thank God for antagonistic cooperation, and tell this story: What this movement does is immoral and base, a cowardly, carnivorous thing. Many thousands of artists are suffering because of it. It has malignant intentions for our country, and will rot the heart of us to achieve them. But if we are brave. If we refuse to be silenced. If we recruit more and more artists to this cause, we will endure this darkness, we will emerge from it, and we will triumph in the light. “Indeed,” says Murray, “...in the final analysis the greatness of the hero can be measured only in scale with the mischief, malaise, or menace he can dispatch.”

So in my own small way, I’m going to try and be great. I’m going to do that, instead of filling my daughter with dread over a nice meal on a bright San Francisco day. I will not die because of everything they have done to me, my dear and beautiful child. I will live for the very same reason.

I closed my last essay with a poem. I’ll close this one with a song I chart my course by.

Unsinkable, by Sail North

Unsinkable

Aim high, swing hard, leave it out there, no regrets

My blood is in the water and the sharks are taking bets

They circle are waiting for my final breath

But they won’t see me drown

I hoist my sails for the treasure in the sea

The winds that blow behind me take me where I’m supposed to be

I’m raising hell for the ones who don’t believe

Their words can’t drag me down

When the wind rips the tide

I will sail

Reach the other side

Let the storm roll on wild

I was born for this

I’m unsinkable.

Nota bene 1: My fundraiser, Speak up for a Silenced Artist, has raised money for a staging of my play, The Macbeths. Because of the cancellations and to prevent further harassment, I cannot share specifics, but these donations will be put to use in the designated way.

Nota bene 2: Alluded to here is the concept of “soul murder,” which was “first used in the legal code of Saxony in the early 19th century and later by playwrights Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg to describe the destruction of a person’s vitality or love of life.” The term became more commonly known through the work of psychoanalyst Leonard Shengold in his 1989 book, Soul Murder: The Effects of Childhood Abuse and Deprivation.

The Toll of Cancellation on the Human Spirit

On December 18th at 7pm EST, we will explore the human cost of cancellation, the spiritual and emotional dimensions that often go unseen, and the importance of building a culture where disagreement does not mean disposability. Our guest Mary McDonald-Lewis will share her story, her losses, her resilience, and her hope for a better future—one marked not by fear, but by exchange, openness, and shared humanity.

Text FAIRFORALL to 707070 to donate to FAIR’s 250 for 250 Campaign.

We welcome you to share your thoughts on this piece in the comments below. Click here to view our comment section moderation policy.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Fair For All or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diversity of voices and encouraging compassionate and good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

When going thru a very dark time, I fell upon a message from Jesus: "I don't allow this to happen to hurt you. It is to strengthen you." But we need constant reminders to not give up. This essay was a beautiful example. Thank you, continued prayers for this journey.

I know Mary personally and respect and regard her beyond measure. While we may not agree on every opinion, why should we, or even strive to? Debate like art is by design meant to expand our thinking, challenge our assumptions and especially those ways of thinking we were merely exposed to in our formative years. It should allow and encourage us to decide for ourselves, then rethink and decide again. When did we lose the ability to respect others opinions and thoughtfully consider them, whether or not we agree with them, before or after the considering? How do we regain that for our communities?