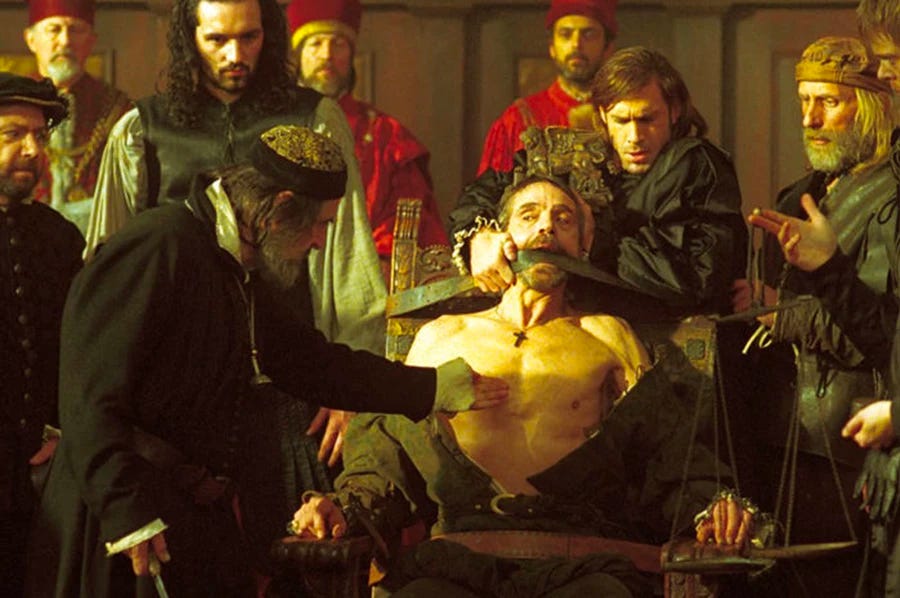

In Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, a cash-strapped nobleman named Antonio borrows money from Shylock the moneylender. As collateral, Shylock stipulates a pound of flesh. Antonio ends up in court, strapped to a chair, with Shylock’s blade pressed against his naked chest. Portia, the story’s female protagonist, turns the tables in the nick of time. Disguised as a man and acting as Antonio’s lawyer, Portia agrees that Shylock can take the pound of flesh, according to his ironclad contract. However, she says, that same contract says nothing about blood. If Shylock cannot cut out the flesh without spilling the blood, he cannot collect.

It's sometimes said that Portia got Antonio off on a technicality by adhering to the strict and literal wording of Shylock’s contract. The same things are now being said about Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito with respect to the constitutionality of abortion. Alito styles himself an “originalist,” meaning he wants to stick—some would say rigidly—to the exact meaning of the constitution as it was written in the eighteenth century. It’s true that the constitution says nothing about abortion, but it also makes no mention of women at all, since women were not considered citizens when our republic was founded.

Following the letter of the law, Justice Alito is correct. However, if he followed the spirit of the law rather than the letter, he’d have to see what the right to privacy guaranteed in both the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments truly means. In The Merchant of Venice, Portia tries to bring what she calls “the quality of mercy” into her discussion of the situation between Antonio and Shylock. I would argue that in the case of the right to abortion, mercy matters too.

Like Shylock, Alito wants an ironclad contract: If a woman gets pregnant, then she must deliver. Portia, noting Shylock’s contract stipulates flesh, but not blood, would give Justice Alito his due while also stopping him from slicing out women’s rights. Up to the last moment in the play, Portia appears to be, like Alito, sticking to the letter of the law. Like him, she explores each side of the argument, acknowledging Shylock’s sense of justice before pointing to what she believes is a greater justice. In an argument about abortion, I believe she’d point to photos of dismembered fetal arms and legs and admit, “This could have been me! Those fighting for the legal right to kill a babe in the womb were all safely delivered! Each slaughtered infant might have become a whole, healthy human. Knowing this,” she would ask, “what on Earth justifies the destruction of a helpless, growing human?”

Answering her own question, Portia would likely then say “An ultrasound”—an ultrasound revealing the fetus’s brain is gone and the rest of its body is decaying, sending poisons into the woman’s womb. That’s how Savita Halappanavar, an Irish dentist, died of sepsis and an e-coli infection in 2012, when University Hospital Galway refused her an abortion. At four months, the fetus was braindead, but still had a heartbeat. The heart of a non-viable fetus can keep beating long after the rest of it is decaying, sending the pregnant woman into sepsis—in which an already-present infection triggers more infections, leading to organ damage and death. A woman in septic shock expires in agony, often with a fever of 105º or higher.

That’s how Mary Wollstonecraft died, and it’s how women in Poland are dying now—because doctors are refusing abortions until the heartbeats of their braindead fetuses stop.

“But,” Portia would add, “what about a normal fetus? A fetus with a healthy brain as well as a beating heart? A fetus that could make it to the finish line? Does the court have a right to force a woman to incubate that baby? Should her unborn fetus develop at all costs? What if she’s thirteen? An incest victim? A drug addict who can’t get clean? A woman repeatedly raped by a violent partner? Just desperate?” In The Merchant of Venice, Portia’s reasoning speaks to both sides:

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

Mercy, she’s telling Shylock, is a gift—and one that keeps on giving. The one who gives mercy is happy, as is the receiver of mercy. Is it not unmerciful to force women to bring to term unwanted, even hated, pregnancies? Pregnancies destroying their health and sometimes killing them? If we fail to protect the drug addict who only realizes she’s pregnant at four months, or the teenager in denial, or any woman who for whatever reason cannot bear to give birth—we’re back with Shylock’s knife, poised for the kill.

Ironclad contracts lack the quality of mercy; they spill blood.

Portia tries and fails to instill the quality of mercy in Shylock. The desire for control overwhelms him as it overwhelms both sides of the abortion debate, rendering both deeply hurt, profoundly outraged groups incapable of mercy. The take-no-prisoners approach of both “Shout your Abortion,” and “Abortion is Murder” prevent all of us from hearing and imagining the hopes and fears of opponents. But the ability to do so, as Portia argues, forms the much-prized and extremely rare quality of mercy. This mercy fits a king better than his crown, she says, and finally—in a line I wish the groups calling themselves “pro-life” could hear—she says that such mercy is “an attribute to God himself.”

It might take a god to sympathize with both sides, but it’s possible to defend the right to abortion without attacking those who still believe it is immoral. It’s possible to imagine where Ben Shapiro is coming from, thinking the end of Roe saves thousands of human beings. For many reasons, he really believes abortion is murder. Can he return the favor, however? Would he still take his position if he were able to imagine himself as a single mother of two with diabetes and heart disease, who felt she just could not bear another birth even if she were likely to survive it?

The question is whether he could stand to imagine being that woman, and whether women needing abortions can bear to imagine his feelings and to respond to them. The horror in doing so, for each side, is the possibility of losing oneself—of losing one’s beliefs, like a Stanislavski method actor. What if Ben Shapiro thought himself into the mind of a real murderer? What might he believe about abortion after that experience?

If Ben Shapiro thinks callous narcissism is behind abortions, he’s not entirely wrong. I knew a woman who tittered and told me, as we were getting ready to go to the beach with our families, “Oh, I couldn’t be bothered with contraception.” She mentioned two abortions with no apparent display of emotion or regret. I felt a wave of revulsion. In my sixty-five years I’ve seldom heard a more heartless remark. But she doesn’t represent most women having abortions. In her 1987 essay, “We Do Abortions Here,” Sally Tisdale, who worked in an abortion clinic for years, mentioned “the fine print”—those who’d been on the Pill and gotten pregnant anyway—as well as the hopelessly incompetent: She describes a “sixteen-year-old uneducated girl who was raped,” has gonorrhea, and asks “When’s the baby going to grow up into my stomach?” It turns out the girl thought the baby hatches out of an egg in a woman’s stomach. This traumatized girl with gonorrhea—should she, Ben Shapiro, be made to give birth to an infected child whom no one is willing to care for?

It is these women, those who are not living but existing from day to day—beleaguered by poverty, ignorance, and drug abuse—who suffer the most. So often, undesired children themselves, born to teenage mothers too exhausted by life to raise them, fall into familiar patterns. These are the women who aren’t shouting out their abortions, but hoping to survive somehow. The women who are often heard—educated women with an income—can usually find some way to have an abortion whether it’s legal or not. It’s a luxury to have the ability to take off work to make signs and hold them up during a rally. Other women—the ones who can’t speak for themselves, who can’t afford paint for their posters, or car fare, or babysitting money, who can’t attend the rally, will be destroyed.

Absolute justice, Portia observes, would condemn all of us; we all want a mercy we don’t deserve, and in longing for mercy we learn to give it to others:

In the course of justice, none of us

Should see salvation: we do pray for mercy;

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy.

I doubt all Americans will ever see alike on this hottest of issues, but a majority favor the right of a woman to choose, and to have her own regrets or relief. Flo Kennedy famously remarked, “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament,” and a notable element of her comment is the religious language. The Ben Shapiros of the world are fueled by a form of religion not given to reflective considerations of motive. For him and for so many it’s enough to call abortion murder—even to call it genocide.

The bigger issue remains, for both sides in the abortion conflict, the notion of one single truth. Both sides allude to the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm.” The reality appears to remain that doing abortions can sometimes do harm. Usually not, however. If statistics and word of mouth mean anything, abortions for women who want them remain the better choice.

Discovering her birth mother intended to abort her, Clare Culwell, who lived because the physician performing the abortion didn’t realize she was still in the womb after he’d removed her twin, argues from her serendipitous survival that all abortion is murder. For me, things aren’t so simple. I’d never begrudge my mother the abortion she might have had to get away from a man who hit her and a way of life suffocating her. Even so, I’m glad I exist. Life is crammed with such paradoxes. Returning to Shakespeare’s Portia: like me, she’d admit that abortions are sad—but there are sadder situations.

By disallowing abortion, the court fails to protect those who need protection the most—like the poster child for the original Roe v. Wade abortion debate, Gerri Santoro. A 1964 police photo first published in Ms. Magazine in 1973 shows what appears to be her excruciatingly painful death after a botched abortion. Alone in a hotel room, she crouches in a fetal position, bloody towels between her drawn-up legs. To deny legal abortions reinforces the idea that women’s role is to “give” birth—even if doing so means giving away her life; bleeding to death from a back street abortion if she cannot face producing that pound of flesh.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diversity of voices and encouraging compassionate and good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

Join the FAIR Community

Become a FAIR Volunteer or to join a fair chapter in your state.

Join a Welcome to FAIR Zoom information session to learn more about our mission, or watch a previously recorded session.

Sign the FAIR Pledge for a common culture of fairness, understanding and humanity.

Join the FAIR Community to connect and share information with other members.

Share your reviews and incident reports on our FAIR Transparency website.

Read Substack newsletters by members of FAIR’s Board of Advisors

Common Sense – Bari Weiss

The Truth Fairy – Abigail Shrier

Skeptic – Michael Shermer

Habits of a Free Mind – Pamela Paresky

Journal of Free Black Thought – Erec Smith et al.

INQUIRE – Zaid Jilani

Beyond Woke – Peter Boghossian

The Glenn Show – Glenn Loury

It Bears Mentioning – John McWhorter

The Weekly Dish – Andrew Sullivan

Notes of an Omni-American – Thomas Chatterton-Williams

I hope that I can some day misunderstand a situation so thoroughly that FAIR will give me a platform to tell everyone about it. There’s so much to disagree with here, but I’ll just mention two.

First, as Elizabeth said below, SCOTUS did not ban abortion. Melissa says that Alito is hungry for power, but what the court essentially decided was that it wasn’t up to them to decide for the whole nation on the abortion issue. There’s this weird thing going on right now where people think that it’s “authoritarian” that the whole country now gets a say on the issue, instead of 9 people.

Second, running throughout the whole essay is this idea that everyone is thinking about this issue in black and white, but Melissa has a more nuanced view. It’s quite a selective nuance, however, as she takes on a more black/white stance when it’s convenient. For example, she links to a study that says the majority (61%) of Americans favor the right of women to choose. So, pro-abortion, right? No. Here are the two choices from the study: legal in all/most cases vs illegal in all/most cases. In other words, those who want abortions without exception are grouped with those who want abortion with exceptions, and those who want no abortions whatsoever are grouped with those who want no abortions, with some exceptions. This distinction is fundamentally meaningless because most Americans are somewhere in the middle. Most Americans have a more nuanced view, despite what Melissa says.

Based on the essay, her “more nuanced” view involves misunderstanding jurisprudence, straw-manning the entire populace, and dragging out every exceedingly rare pro-abortion trope. Nuance is also lost when she repeatedly talks about getting pregnant as something that just seems to “happen” to women.

She begins the last paragraph with, “By disallowing abortion, the court fails to protect those who need protection the most”. As stated above, they didn’t “disallow” abortion. Beyond that though, one thing I’ve noticed more recently is that pro-abortion people used to at least mouth the words that the unborn child exists and should be considered, but that time seems to be long gone. Now there is never any mention of the unborn child (or fetus, if you want to conveniently dehumanize it). Its worth is literally nothing in today’s discourse. You could argue that the unborn child’s life is worth less than that of the mother, but to ignore it entirely is the sort of black-and-white thinking that Melissa is taking part in while simultaneously railing against.

I could go on and on, but the sort of sloppy thinking displayed in Melissa’s essay gets us nowhere. She should have a right to say it, and I appreciate that FAIR allows for diversity of thought, but this is particularly weak. I look forward to seeing more worth reading in the comments section than the article itself, which seems to be happening more and more around here, as of late.

EDIT: fixed typos

This is a moronic piece of cluelessness. I love the beginning, looking for deep intellectual meaning, but you failed within the first comparison. Alito and SCOTUS did not provide mercy -- they provided noting other than the rule of law. Your weak comparison is amateurish at worst, naive at best. No rights were stripped, only a bad decision removed from the history books, delivered to the States and We The People as the law requires to make a decision on this gravely important matter. Of course this does not fit into your brilliants but lacking presentation of a great play comparator. You are better than that... especially considering your writing skills are fantastic.