DEI can be a good thing, but it often isn't

This week on our Substack, Angel Eduardo writes about diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings, “their startling inefficacy and counterproductivity, and the havoc many of them (particularly those in the vein of Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility) [tend] to wreak on workplaces.” He describes his own experiences in a DEI training, and how a more pro-human approach to incidents of bias, discrimination, or misunderstandings at work and elsewhere would fare much better than current trainings on offer—however well-intentioned many may be.

The issue wasn’t them or their intentions; it was that the framework they were using primed us to emphasize division and cultivate discord. It was a foregone conclusion for everyone around me that something horrible had happened in that exchange with the office assistant. As they say, the question was not whether racism occurred but how it had occurred. However, this threw so many other possibilities and potential solutions out the window.

It went beyond someone with a hammer always finding nails; it was like someone with a hammer owning a nail factory.

Schoolchildren Are Not ‘Mere Creatures of the State’

For Commentary, FAIR Advisor Robert Pondiscio writes about “the notion that the state must not interfere with parents and their right to direct their children’s upbringing and education,” and how “the state seems increasingly inclined to relitigate the matter—if not in court, then in practice and policy in America’s public schools.”

There have been myriad recent examples of schools imposing their staffs’ ideological preferences, and in so doing being disingenuous or openly dishonest about critical race theory, trangenderism, “social and emotional learning” programs, and other controversial aspects of school curriculum and culture. The picture that has begun to emerge is of an education establishment straying beyond its remit, emboldened to ignore parents, and determined to subvert local control of schools to advance a social-justice agenda. “It’s infuriating, it’s harmful to children, and it’s unacceptable,” says Vernadette Broyles, an attorney and the founder of the Child and Parental Rights Campaign. “And it’s contrary to law.”

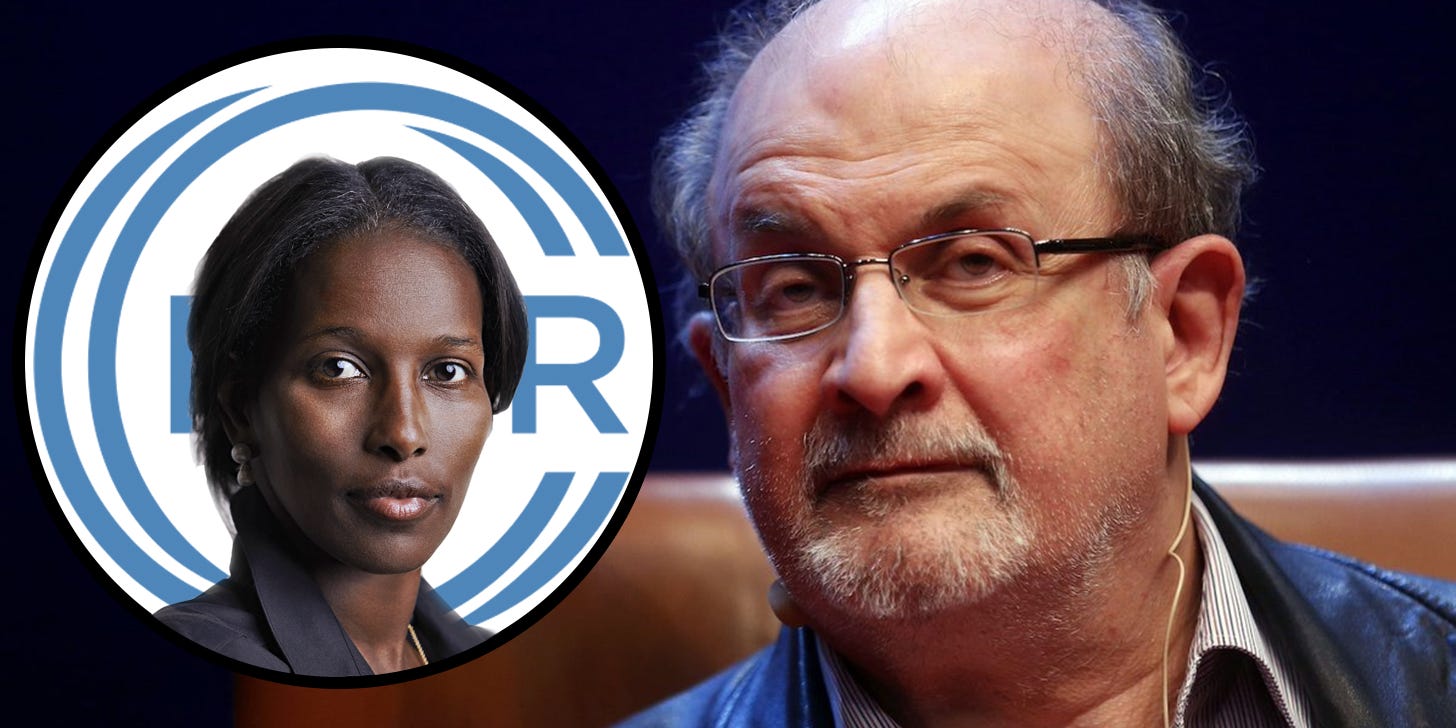

I once wanted to burn ‘The Satanic Verses.’ Now I weep for Salman Rushdie.

For the Washington Post, FAIR Advisor Ayaan Hirsi Ali writes about her past as “a teenager in Kenya, a Muslim with the righteous convictions of the young, eager to obey the edicts of the highest religious authorities,” which caused her to want to burn Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and wish for his death. Her life would lead her on a different path, however—one that would end with her “shattered” after the recent knife attack on Rushdie in Chautauqua, New York.

In the intervening years, I came to realize that the religion of my youth was an oppressive, dangerous version of the faith. Forced into marriage in the early 1990s, I fled to the Netherlands, where I successfully sought political asylum. There, I studied political science, later becoming a member of parliament. And I watched with mounting anger, and horror, as radical Islam pursued its war on modern civilization — perhaps these words can still be said, on Western civilization.

I cherish the freedoms afforded by Western civilization, and I especially cherish the freedom to speak freely. That is why the attack on Rushdie, beyond the terrible fact of his injuries, is so abhorrent.

Bill Maher is saying what liberals are thinking

For The Spectator, FAIR Advisor James Kirchick

We must not let the brutal censors win

For The Equiano Project, FAIR Advisor Inaya Folarin Iman explains her organization’s delayed response to the recent attack on Salman Rushdie, and that “whilst every event like this rightly unleashes outpourings of shock and devastation, impassioned defences of freedom of speech, calls on all to stand up for liberal values, and so forth, there is now an eerie repetitiveness to our immediate reactions to these awful occurrences.”

This attack comes more than three decades since Ruhollah Khomeini, the then supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie's assassination… And since then, rather than spark a renewed cherishing of our sacred values, we have instead, accepted and institutionalised much of the logic that underpinned the actions of those brutal censors. We now widely proselytise about how certain ‘identities’ must be ‘protected’ from offence, and that certain identities must be treated differently due to their religious, cultural or racial background. We commonly say that the prevention of offence or the preservation of ‘emotional safety’ should take precedence over the universal value of freedom of speech. We assert that hurtful words can be reasonably equated with violence. Further, those that argue for the widest possible boundaries of freedom of speech are viewed with suspicion, as uncool and archaic in some way.

James Baldwin's Radicalism

For Persuasion, Sahil Handa writes about the profound impact James Baldwin’s writing had on him as “a skinny, 17-year-old Indian boy with braces,” and the ways Baldwin “taught [Sahil] something about love, and that necessarily colored everything that he had to teach [him] about color.”

Baldwin loved America in the same way that he loved himself: fiercely, relentlessly and, most of all, critically. Contained within the country’s ruinous past was a magnificent potential that would never be fulfilled by reifying the categories of color that had trapped it in a racial hierarchy since its birth. Racial progress needed to contend with both catastrophe and reality at once; it needed to recognize the political fact of skin color—and the suffering it would continue to bring—while insisting that “the value placed on the color of the skin is always and everywhere and forever a delusion.” This demanded a magnanimity from blacks that could hardly be justified by American history. Yet it was, Baldwin saw, the only way blacks could seize their own freedom in a country that had never previously accepted them. “I know that what I am asking is impossible,” he wrote. “But in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least that one can demand.”

America’s Fire Sale: Get Some Free Speech While You Can

For The Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan writes about her experience signing the Harper’s letter, the resultant backlash to it, and the increasingly hostile discourse and culture surrounding free speech and free expression, prompted by the recent attack on Salman Rushdie.

Whenever a society collapses in on itself, free speech is the first thing to go. That’s how you know we’re in the process of closing up shop. Our legal protections remain in place—that’s why so many of us were able to smack the Trump piñata to such effect—but the culture of free speech is eroding every day. Ask an Oberlin student—fresh outta Shaker Heights, coming in hot, with a heart as big as all outdoors and a 3 in AP Bio—to tell you what speech is acceptable, and she’ll tell you that it’s speech that doesn’t hurt the feelings of anyone belonging to a protected class.

The Polarization Spiral

For her Substack, Spiritual Soap, Salomé Sibonex writes about how “the threat of backlash adds a little armor to your every word,” and offers a “home remedy for avoiding this sickness that leaves you silent. Too weak a defense eventually fails, but push too hard and you end up a puppet that moves in reverse to what you oppose.”

It’s the fear of pain that gives it power. If I didn’t fear suffering, I wouldn’t have avoided writing this essay for months. A threat is the possibility of pain, not the certainty; it’s the possibility of being accused of the day’s latest -ism that subdues you, not the certainty. There’s peace in definite destruction. When the option to escape is gone and fear is useless, the threat no longer controls you.

There’s your existential cheat code.

The Emotional Liquor of Offence

For Law & Liberty, Helen Dale writes about her own experience “being the bad person for the crime of writing a novel,” and “the extent to which Rushdie represents the extreme tip of a very large iceberg of cowed and cowering writers and publishers, and not only because of radical Islam.”

Yes, Rushdie and other authors who’ve been killed or driven out of Muslim countries are in the most danger. Joseph Anton provides a grim rollcall of names and narratives. But what was done (and continues to be done) to Rushdie and others like him has also legitimised the blaming of writers for what they write rather than the blaming of readers who take offence at what they read. This is nothing more and nothing less than gross abdication of personal responsibility on the part of readers (and, sadly, non-readers; both Rushdie and I have encountered people proud not to have read a single word of what we’ve written).

For audio versions of our FAIR News and FAIR Weekly Roundup newsletters, subscribe and listen to FAIR News Weekly on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or via RSS feed.

Join the FAIR Community

Become a FAIR volunteer or to join a FAIR chapter.

Join a Welcome to FAIR Zoom information session to learn more about our mission, or watch a previously recorded session in the Members section of www.fairforall.org.

Take the Pro-Human Pledge and help promote a common culture based on fairness, understanding, and humanity.

Join the FAIR community to connect and share information with other members.

Share your reviews and incident reports on our FAIR Transparency website.