At Fair for All, we aim to publish a wide range of pro-human voices, whether they’re seasoned authors or first-time writers with something important to say. If you would like to submit your writing to us, please visit our About section and scroll to the bottom for our submission guidelines.

We hope you enjoy our inaugural essay below from FAIR member Alice Irby.

I grew up in a segregated society. I worked to overcome it. I don’t want to go back to it.

I was born in 1932, in a small, segregated town in North Carolina during the worst year of the Depression. At that time, we lived under the “separate but equal” doctrine established by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1954, this doctrine was overturned in Brown v. Board of Ed., which required schools and colleges to integrate. Despite this ruling, it was not until the mid-to-late 1960s that schools in my town and many others across the country were actually integrated. During these intervening years, time and again, I found myself at the intersection of discrimination and tolerance; of segregation and integration; of the pull of tradition and the desire for change.

In 1958, I became the Director of Admissions at The Woman’s College (WC) of the University of North Carolina, now UNC Greensboro. I eagerly sought out able young women of color at segregated high schools, encouraging them to join the other 2,500 women at WC. It was important not just that they be admitted, but that they would successfully meet WC's high academic standards. Over time, minority students, both female and male, grew in number. Today, UNCG has an African-American Chancellor, and boasts the best record in the North Carolina college and university system for enrolling, retaining, and graduating students from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Integration works!

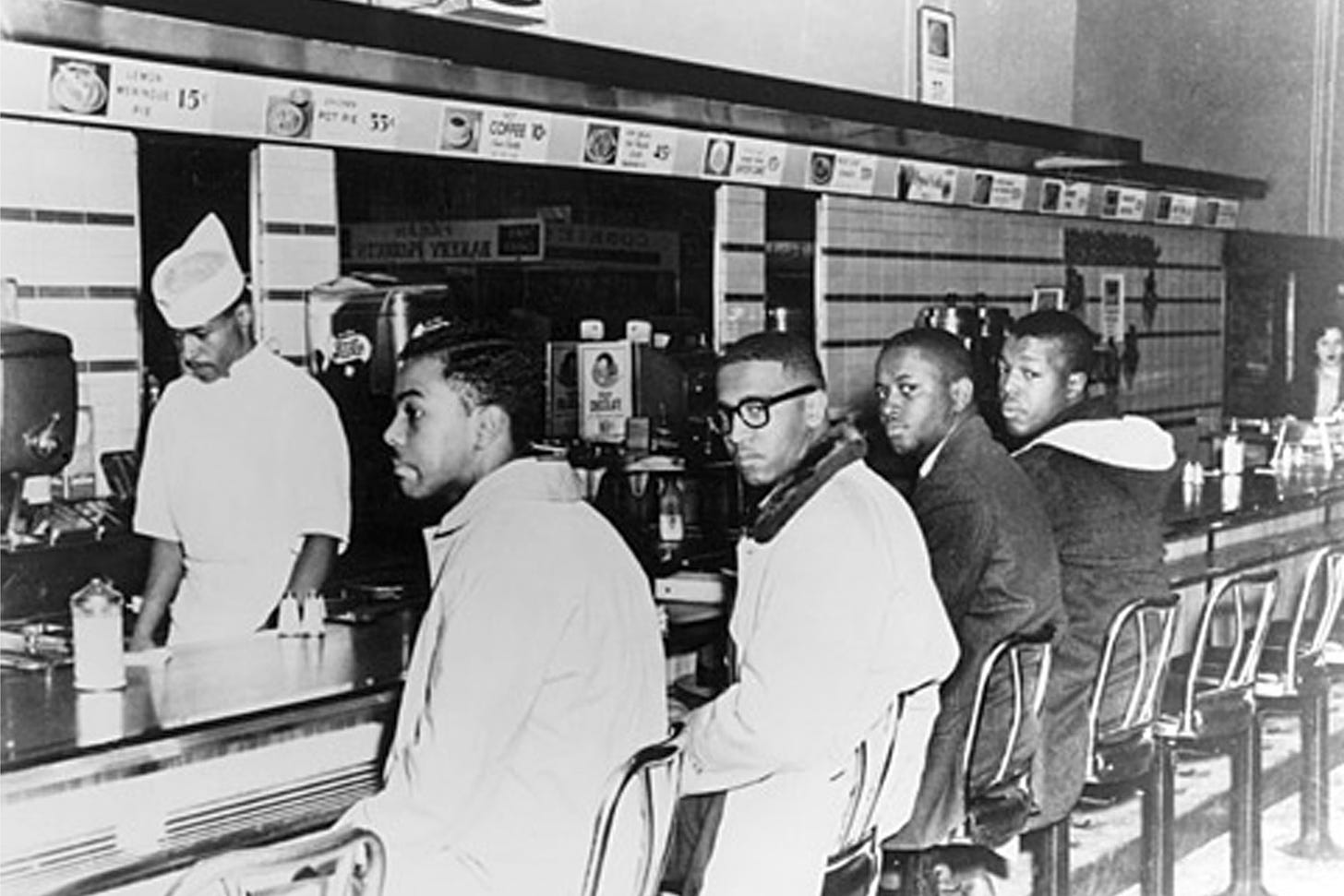

Early in 1960, a few blocks away from my office at WC, in the middle of downtown Greensboro, a group of young African-American men from NC Agricultural and Technical College sat at the Woolworth Lunch counter, waiting to be served. They continued to sit at that counter, even after being told they would be denied due to the color of their skin.

At that time, I became involved with a group of students at WC who were active in these civil rights protests. Some students in this group faced expulsion after breaking WC’s honor code by falsifying their destination away from campus. When several of these students approached my colleagues and me for help, we petitioned the Chancellor on their behalf. We believed it was important for them to participate in the developing civil rights movement by supporting the students sitting at the lunch counter.

Day after day, the young men came to the Woolworth’s lunch counter. Word spread around town, then around the country. The Chancellor was in the crosshairs of competing forces in the community and state. He spoke to the 2,500-member student body, calling for calm and order, and reaffirming the importance of free speech and debate on our campus. The students who violated the honor code were not punished—except that they had to call their parents to inform them of their actions.

Those young men—and the thousands of students and citizen supporters in Greensboro—bolted over the hurdles of the “separate-but-equal” doctrine that had justified discriminatory laws nationwide since 1896. Through peaceful, dignified protests, these courageous young Americans ignited similar protests elsewhere, giving rise to a civil rights movement that created change—positive, lasting change.

Awakened by the inspirational voice of Martin Luther King Jr., guided by the political skills of President Lyndon Johnson, and supported by the Senator from the “land of Lincoln,” Everett Dirksen, Americans from across the political spectrum came together to support the passage of landmark legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which guaranteed civil rights and liberties to all, regardless of their immutable traits. I recall, at the time, the air was electric, the discourse exciting, and the halls of Congress alive with optimism. I saw with my own eyes that dreams can come true when there is good will, trust, and bipartisan leadership.

I was present in the Johnson Administration and watched as it introduced important initiatives such as the War on Poverty, Head Start, the National Teacher Corps, and the Job Corps; many of these programs continue to help those in need. I was involved in establishing the Job Corps, a residential program for youth between the ages of 16 and 22 who were out of school and work. The purpose was to jump start a new beginning for them by providing a hand-up, not a hand-out. The major victories of the civil rights movement began opening doors of opportunity and expanding educational access, making it finally possible for a multitude of students of color to attend college and enter professional careers.

So many people take these advances in civil rights for granted, without recognizing that they were achieved only through the labor, persistence and moral courage of thousands of people who stood up for what is right. These dramatic positive changes paved the way for all Americans to fulfill their human potential.

Many of us who labored in the civil rights movement were inspired by Martin Luther King Jr. I heard him call on us to respect others, not suppress them; to embrace diversity, not discriminate against each other; to improve our country, not tear it apart. Hope. Dreams. Fairness. Equality. The coming together of diverse people from all walks of life to work toward fulfilling the promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness as promised by the Declaration of Independence. The Civil Rights movement opposed bigotry by relying on hope, opportunity, and cooperation. We did not succumb to anger, dissension, despair, or intolerance.

Now, as I look around, I am frightened. I see hate, not hope; dissension, not dreams; tribalism, not unity. The Civil Rights movement fought for the principle of equal opportunity, regardless of race. Today, those who call for “equity” actually support discriminating against individuals based on race to bring about equal outcomes between racial groups.

Change is often a slow and gradual process. It is natural for young people to be impatient with reform and social progress as they instinctively seek perfection now. Perfection in a society of imperfect human beings, however, will always be an elusive goal. Nevertheless, we must move forward with the moral imperative to stand against discrimination of all kinds as best we can. We must continue the work of the Civil Rights movement toward a society of fairness, understanding, and a future where people are judged not on the color of their skin, but on the content of their character.

I am a follower of Martin Luther King Jr., not Ibram X. Kendi. I do not believe that present discrimination is the remedy for past discrimination. Our nation was not founded on slavery, but on ideas that paved the way for the abolition of slavery. It is because of these beliefs that I support FAIR, a multiracial, non-partisan organization dedicated to principles of fairness, tolerance, and equality—a community whose advisors and members stand tall in reaffirming our common humanity and who show courage in combating forces of intolerance, racism, and injustice. I stand not only for our founding ideals and aspirations, but also for more eternal verities—compassion, respect for all, kindness toward others, and love of mankind. I choose the optimism of King over the pessimism of the neo-racist “anti-racism” of today.

We are all one race—the human race. We laugh, cry, and bleed the same. America is a beautiful multiracial mosaic, and it grows more diverse with each passing year. In our present moment, it is especially necessary to hold true to the values of fairness, understanding, and humanity that shaped the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. These are the values that can help to heal our societal wounds, restore excellence to our educational institutions, ensure justice and equal rights for all, and garner our many diverse strengths as we seek, as ever, a more perfect union.

Alice Irby helped establish the Job Corps, and in the 1970s joined Rutgers University as the first female Vice-President of a major university. Irby’s book, South Toward Home, documents her journey during periods of turbulent societal change.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diversity of voices and encouraging compassionate and good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

Join the FAIR Community

Click here to become a FAIR Volunteer or to join a fair chapter in your state.

Join a Welcome to FAIR Zoom information session to learn more about our mission by clicking here. Or, watch a previously recorded session click here to visit the Members section of www.fairforall.org.

Sign the FAIR Pledge for a common culture of fairness, understanding and humanity.

Join the FAIR Community to connect and share information with other members.

Share your reviews and incident reports on our FAIR Transparency website.

Read Substack newsletters by members of FAIR’s Board of Advisors

Common Sense – Bari Weiss

The Truth Fairy – Abigail Shrier

Journal of Free Black Thought – Erec Smith et al.

INQUIRE – Zaid Jilani

Beyond Woke – Peter Boghossian

The Glenn Show – Glenn Loury

It Bears Mentioning – John McWhorter

The Weekly Dish – Andrew Sullivan

Notes of an Omni-American – Thomas Chatterton-Williams

Amazing courage. I remember the progress that we made in the 1990s up through 2014 having worked on cross-cultural mentoring and reconciliation in the church. Having elected Obama it seemed like we were at a new level in our country establishing the full MLK vision. Unfortunately, many under 30ish believed lies on social media and from colleges set on CRT. We need your story to be told to get us back on the right track.

People may underestimate the courage it took to do the things Ms Irby did—doubly so her being a her.

Now aside re: the war on poverty. That’s a joke. How do you win a war on poverty by constantly importing poor people? You don’t. It was a “war” always meant to be lost and ongoing. Its a jobs program. Which will happen first ? We run out of money (already happened) or the third world run out of poor people? We have no border