The Dialectic of Freedom

America exists as an outgrowth of the dialectic of freedom, with profound American experience and history existing on both sides.

Freedom, yes. But freedom of, or freedom from? In a country founded upon the assumption of “certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” it is that question that more and more has come to polarize the subject of freedom across the generations. Can our conceptions of freedom be reconciled? Can we consider the imperatives of liberty in terms that dignify the concerns of all?

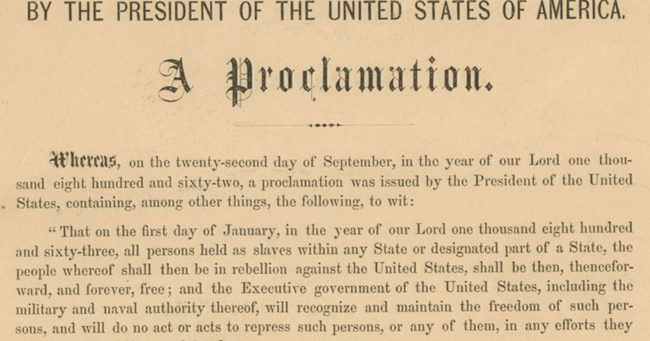

Freedom and equality, so foundational to the American experiment, present a natural tension between the two of them. For in perfect freedom, those with certain advantages of birth or skill may easily find themselves in a superior station to that of their neighbors. This plays itself out in many ways. But in the very beginning of the American experiment and for 89 years to follow, the inherited privileges of race sacrificed the liberty of one group of people to the predacious liberty of another. Freedom from bondage for enslaved Africans was subjected to the liberty to own people as human-beings. As plain a contradiction of both the principles of freedom and equality as spelled out in the Declaration of Independence as this was, there was a debate that roared all the way up into the point of brutal and bloody Civil War in which many nuances and caveats were marshaled in defense of the more circumscribed view of freedom and equality put forward by defenders of the “peculiar institution.”

One could not take literally Jefferson’s claim that all men were created equal because Africans (taken from their homeland, prohibited from literacy, and subjected to the debasements of enslavement) were plainly not the equals of white men. And therefore, is the liberty of white men, for whom the Declaration was properly written in this view, not diminished by the curtailment of their right to enslave? It was this position Abraham Lincoln wryly lamented in his second inaugural address, when commented that “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.”

Today we would nearly all share Abraham Lincoln’s tragic bemusement at the conspicuous contradiction in the argument for slavery made on behalf of liberty. But many of us of a liberal and progressive disposition would react with incredulity to those conservatives and libertarians amongst us who might employ a similar logic in opposition to the expansion of government benefits that redistribute the wealth and labors of the American people. As Senator Rand Paul once said, “with regard to the idea whether or not you have a right to health care you have to realize what that implies. I am a physician. You have a right to come to my house and conscript me. It means you believe in slavery.”

There may have been something unwise in the extremity of Paul’s comparison, yet it serves to highlight the differing Americans views of freedom. The Bill of Rights enumerates certain freedoms of a negative kind: meaning that they are freedoms from the imposition of force and authority against key aspects of American life. The United States Constitution guarantees “the freedom of speech,” the freedom of assembly, the freedom to bear arms, among other rights established for the liberty of individuals. But these were negative rights in the sense that they were rights that prevented the encumbrance of man or government upon other individuals’ ability to assert themselves in these ways as citizens. They were not positive rights in the sense that they guaranteed certain goods that may even be vital to life and the pursuit of happiness, but would require an imposition on the liberty of others to ensure.

Yet even as the emancipation of Black people from slavery dispelled a grievous breach of negative liberty in that it undid the state sanctioned and privately enforced restriction of the speech, assembly and autonomy of millions of people, so too did emancipation reveal the real limitations of freedom in the absence of the material underpinnings of life, liberty and happiness: Black people were freed, but they were freed into poverty. Black people were freed, but they were freed into illiteracy. Black people were freed, but they were freed into continuing exploitation by the lingering plantation elite in the rural south who had previously owned them. A century later, standing before the Lincoln Memorial, when Martin Luther King Jr. shared his dream with America and observed that one hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation “the Negro still is not free,” King claimed this not merely in the context of Jim Crow segregation, but in the context of circumstances in which “the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” On other occasions King would remark that “it’s all right to tell a man to lift himself by his own bootstraps, but it is cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.”

How meaningful is freedom without greater equality? Though it would seem undeniable that one’s personal choices affect the course of one’s life outcomes—one’s “pursuit of happiness”—is there an intellectually honest way to suggest that circumstances we do not choose have nothing to do with these outcomes? That those who suffered in slavery were merely unwilling to overcome the difficulty of their circumstances to achieve the American dream? And though slavery may be over today, are we certain that obstacles are surmounted by will and drive alone in the absence of collective commitments to the common welfare in the form of government action? Yet if this is so, does it not mean that we must always compromise freedom of one kind (the freedom to choose how you spend your money or exercise your vocation) in defense of the freedoms of another variety? (The freedom from poverty, from illiteracy, from health insecurity?)

I do not give answers, but I recommend respect for the question. America exists as an outgrowth of the dialectic of freedom, with profound American experience and history existing on both sides. Let us honor, and break new grounds of freedom together.

We welcome you to share your thoughts on this piece in the comments below. Click here to view our comment section moderation policy.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diversity of voices and encouraging compassionate and good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

Your emphasis on historical examples rather than theory is a first principles approach - excellent.

I see the buried lead in your essay is to identify what things are, and work back to the terms.

Dialects can be a natural part of open discourse: all options are considered through a process: the Socratic method.

But the term itself has come to mean not a process, but a forced choice with one predetermined solution.

Equality is understood as equality of opportunity to maximize potential. Consent is baked in.

Equity is equal outcomes by enforcement. Tyranny is baked in.

In short, Truthtellers focus on what things are, and extract solutions from all options.

Tyrants focus on labels and platitudes to sell the chosen solution.

Freedom for - and - freedom from.

I would love to see this approach on the Dialectics of Freedom gain more traction on a wider scale.

The health care analogy resonated, having two citizenships, USA and France, I have perhaps a unique perspective on this topic. I share the same sentiment about health care actually. In my eyes, health care is simply not a human right, but as a French citizen it’s certainly a source of dignity and pride. That’s the only way I’ll continue to support this system of health care and find satisfaction in it. On the other hand, if I’m told that others are entitled to my ressources, because that they’re right then yes that rings completely different. That’s one of reasons this essay resonated so much for me.