The Body–Mind Connection: How Physiology Is Often Overlooked in Mental Health Care

Gaps in clinical training and time-constrained care often leave physiology out of mental health decision-making, despite its central role in emotional regulation.

FAIR in Medicine is dedicated to supporting the scientific method, viewpoint diversity, and rigorous inquiry in the search for objective truth. We believe that intolerance is the enemy of free and open inquiry and respectful scientific debate. FAIR's advocacy for the rights of biological women and girls in sports and other protected spaces is premised on the need for objective scientific truth, but we also recognize the need to advocate for rigorous scientific inquiry beyond issues relating to gender.

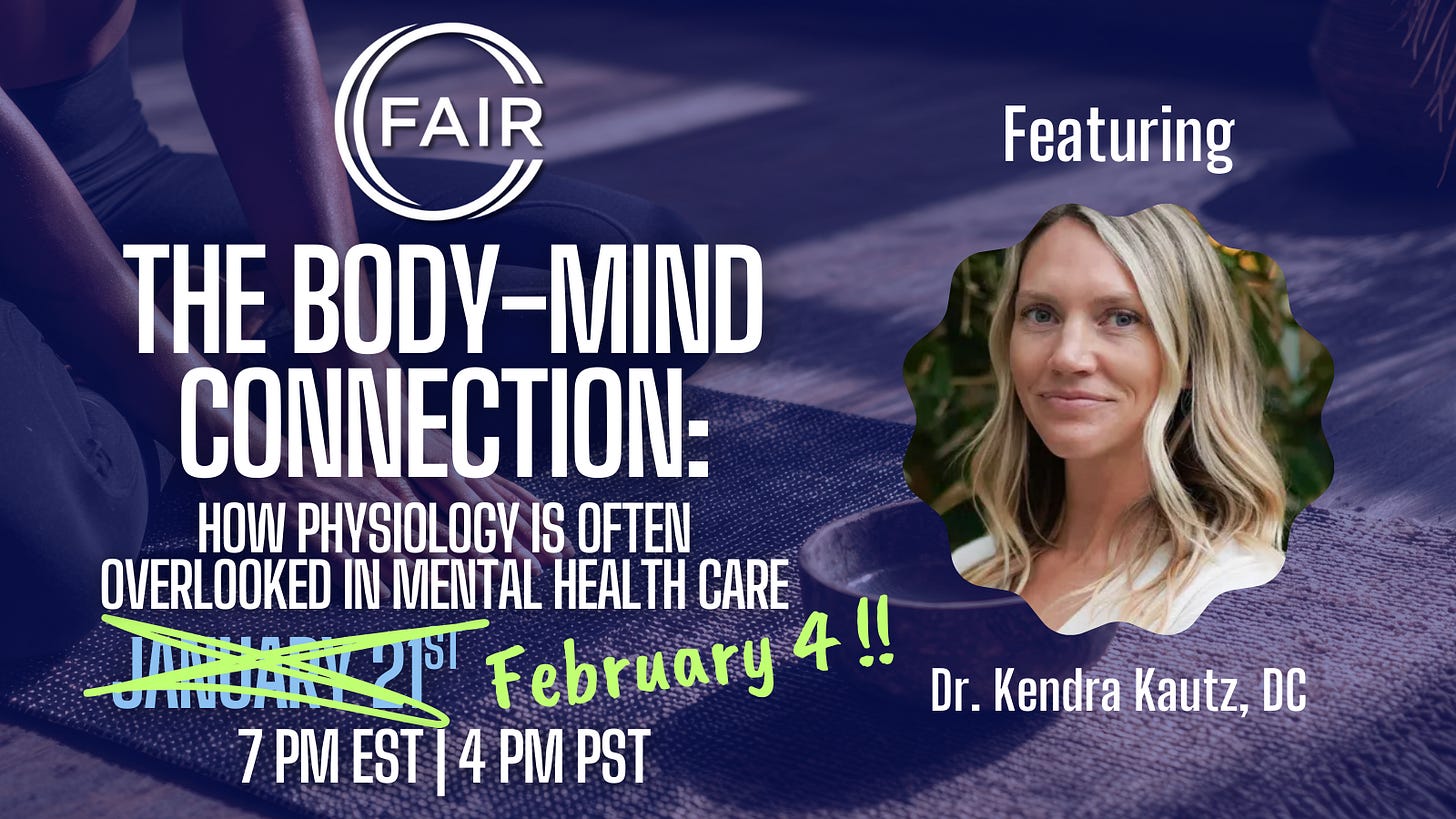

As part of this effort, FAIR is launching a two-part series that will examine how nutrition impacts adult mental health. This essay is the first in that series. In Part II, we will explore how these patterns often occur within adolescence, a period of rapid brain, metabolic, and hormonal development. If this topic interests you, please join us on February 4th at 7pm ET for a webinar discussion with Dr. Kautz.

Going forward, we will explore other areas in which scientific debate and inquiry have been stifled by intolerance to the detriment of doctors and patients.

Every day, millions of Americans receive prescriptions for mental health concerns—anxiety, depression, panic, migraines, fatigue—often without a meaningful discussion of sleep, nutrition, stress physiology, or whether the body has the biological resources it needs to function optimally. More than half of American adults now take at least one prescription medication, and many take multiple medications daily, even as rates of mental illness, chronic disease, and metabolic dysfunction continue to rise.

We are intervening more than ever before, yet many people remain increasingly unwell.

What if the issue isn’t that symptoms are being ignored—but that the physiological foundations shaping those symptoms are rarely explained before treatment decisions are made?

This pattern appears repeatedly across different care settings. A postpartum woman struggling with anxiety and physical pain is offered medication without assessing whether pregnancy depleted nutrients critical for nervous system regulation and tissue repair. A woman with panic attacks and migraines tied to her cycle is prescribed pain and anti-anxiety medication without explanation of how hormonal shifts influence immune and neurological sensitivity. A patient with anxiety and infertility is offered ovulation-stimulating drugs without investigation into how stress physiology disrupted reproductive signaling in the first place.

In each case, symptoms are hastily addressed while the biological context driving them remains largely unexplored.

Why Physiology Gets Overlooked in Clinical Practice

This gap does not reflect a lack of scientific knowledge. Rather, it reflects how modern medical training and clinical systems are structured.

Nutrition, metabolism, and stress physiology are primarily taught through acute disease models, within isolated organ systems, and with an emphasis on diagnosis and pharmacologic correction rather than upstream depletion. Within this framework, clinicians are trained to recognize symptom patterns and intervene quickly—often under significant time and reimbursement constraints.

As a result, the complex interactions between metabolic health, hormones, immune signaling, and mental health symptoms are less likely to be thoroughly investigated or clearly communicated before treatment decisions are made. Patients are often offered solutions without being given the biological context needed to understand why those solutions were chosen—or what other contributors may be involved.

How Chiropractic Practice Revealed the Body–Mind Link

This systematic treatment gap became undeniable to me through my clinical practice as a chiropractor, where evaluating the nervous system is central to understanding pain, recovery, and regulation. Early in my training, a chiropractic mentor emphasized that many symptoms commonly treated as purely structural are often driven by underlying physiological or emotional strain.

In school, we were trained to recognize referral pain patterns and red flags indicating serious pathology—such as cancer, appendicitis, or gallbladder disease—and to use neurological findings to localize nerve root involvement or determine when imaging was warranted. What we were not taught was how common hormonal or metabolic imbalances could produce identifiable patterns of muscle weakness, altered recovery, or nervous system dysregulation.

Over time, it became clear in practice that no symptom exists in isolation. Structural, chemical, and emotional stressors continually interact, shaping how symptoms emerge and persist. In mental health, this often means that anxiety, low mood, and impaired stress tolerance reflect underlying biological strain rather than isolated psychological pathology—what I’ve come to recognize as the body-mind link.

Case Study: Postpartum Anxiety and Physiological Depletion

A postpartum mother presented several months after her second delivery with worsening anxiety, low mood, heightened sensitivity to noise, and difficulty sleeping. She described feeling emotionally unfamiliar to herself. Alongside these mental health symptoms, she also experienced persistent back pain and core instability that had not improved with standard strengthening protocols.

What had never been explained to her was how profoundly pregnancy and childbirth affect physiology. Pregnancy significantly increases demands for iron, B vitamins, magnesium, and zinc to support fetal development, placental growth, and expanded blood volume. Labor often involves meaningful blood loss, and postpartum sleep deprivation and breastfeeding further tax the nervous and hormonal systems.

Her labs reflected this cumulative strain: ferritin measured 18 ng/mL, vitamin B12 was borderline low, and magnesium status was suboptimal. Research has linked ferritin levels below 30 ng/mL with increased risk of anxiety, depression, impaired cognition, and reduced stress resilience—particularly in postpartum women.

Instead of this context, she had been offered pain medication for her back and an SSRI for her mood, along with reassurance that her experience was “normal postpartum.” While that statement was technically true, it lacked explanation. Normal does not mean inevitable, nor does it mean untreatable.

When her nutrient stores were replenished and her nervous system supported, her anxiety softened alongside improvements in physical recovery. The change was not psychological or physical alone—it was systemic.

Case Study: Anxiety, Infertility, and Stress Physiology

Another patient in her early 30s presented with persistent anxiety, insomnia, and difficulty conceiving. She had been diagnosed with “unexplained infertility” and told that ovulation-stimulating medication and oral progesterone were the next steps.

Her assessment revealed a consistent physiological pattern. Her luteal phase averaged eight days—shorter than the typical window needed to support implantation. B-vitamin markers were low-normal, fasting glucose fluctuated significantly throughout the day, and progesterone output was low during the luteal phase, when it would normally be expected to rise.

Chronic stress is known to suppress hypothalamic signaling involved in ovulation and progesterone production. These same stress patterns also heighten anxiety, impair sleep, and increase nervous system reactivity—yet this connection had never been explained to her.

Our treatment focus was on blood sugar regulation through nutrition and movement, nutrient repletion with a B-vitamin complex, hormone support using evidence-informed botanical and adaptogenic interventions, and nervous system regulation through chiropractic care. Her anxiety improved, ovulatory patterns normalized, and conception followed.

Case Study: Perimenopause, Panic attacks, and Immune Reactivity

A woman in her early 40s presented with severe migraines and panic attacks that predictably appeared in the days leading up to her period. Each month, she experienced heart palpitations, light sensitivity, and anxiety intense enough to disrupt work and sleep.

She had been told her labs were “normal,” and the primary options discussed were migraine medication and an anti-anxiety prescription—without explanation of why her symptoms followed such a clear hormonal pattern.

In her case, this hormonal vulnerability was compounded by a sustained state of chronic physiological stress that placed ongoing demand on her immune system. This was supported by her history of prolonged sleep disruption, high cognitive and emotional load, and a symptom pattern that closely tracked hormonal fluctuations—suggesting impaired stress resilience rather than an isolated acute trigger.

Estrogen and progesterone help regulate immune signaling, including how inflammatory responses are controlled. When these hormones decline in the luteal phase before menstruation, immune balance shifts, allowing inflammatory signaling to increase. That immune activation can then feed back into the nervous system, lowering the threshold for migraines, panic attacks, and sensory overwhelm. Her symptoms were not random—they were predictable physiological responses to layered stressors.

The Pattern Beneath the Stories

These cases reflect a broader pattern in mental health care: treatment decisions are often made without explaining the biological mechanisms contributing to emotional symptoms, and solutions are frequently focused on short-term symptom relief rather than addressing underlying drivers.

Blood sugar instability, nutrient depletion, sleep disruption, immune activation, inflammation, hormonal shifts, and stress physiology commonly go unmeasured or undiscussed—even though each meaningfully shapes mood, anxiety, focus, and emotional resilience. When these contributors are not explored, medication can feel like the most obvious option—not because it is inappropriate, but because alternative drivers were never discussed.

What Patients Can Ask to Have Evaluated

While no single test explains everything, certain evaluations can offer meaningful insight.

1. Nutrient Status

Several nutrients play direct roles in nervous system regulation, stress tolerance, and neurotransmitter function. Patients may consider asking about:

Iron studies, especially ferritin (not just hemoglobin)

Magnesium (RBC magnesium can be more informative than serum)

Zinc (when indicated by immune, digestive, or hormonal symptoms)

Low or borderline levels in these markers have been associated in research with anxiety, depression, cognitive fatigue, and postpartum mood symptoms.

2. Blood Sugar Regulation

Blood sugar instability is a common and underrecognized driver of anxiety, panic symptoms, irritability, and fatigue. Helpful markers may include:

When blood sugar fluctuates, stress hormones rise, increasing nervous system reactivity and emotional instability.

3. Hormonal Patterns

Hormones strongly influence emotional regulation and nervous system sensitivity. Depending on symptoms and life stage, evaluation may include:

Progesterone and estrogen patterns, particularly in the luteal phase or during perimenopause

Thyroid markers (TSH, free T3, free T4, and antibodies when indicated)

Cortisol rhythm, ideally assessed across the day rather than with a single blood draw

Even subtle hormonal shifts—within “normal” lab ranges—can meaningfully affect mood, sleep, and stress resilience. Estrogen and progesterone regulate key neurotransmitter systems involved in emotional regulation, including serotonin and GABA. Research shows that fluctuations in these hormones across the menstrual cycle and perimenopause are linked to changes in anxiety, mood stability, sleep quality, and stress sensitivity—even when hormone levels fall within standard reference ranges. This helps explain why people may experience significant emotional symptoms despite being told their labs are “normal.”

When Medication May Be Appropriate

Medication can play an important role in mental health care, particularly in acute or destabilizing situations—such as severe panic, major depression with suicidal ideation, psychosis, or anxiety that significantly impairs daily functioning. In these cases, pharmacologic support may be necessary to stabilize symptoms and ensure safety.

Medication may also be appropriate when the foundational contributors that have been discussed within this article have been explored, yet symptoms remain inadequately controlled. For some individuals, neurochemical support may be an essential layer of care.

At the center of this discussion is informed decision-making. Patients deserve a clear understanding of what medication is intended to address, what it may not resolve, and what other biological factors could be influencing their symptoms. That context allows treatment decisions to be collaborative rather than reactive.

When care includes explanation—not just intervention—symptoms are less likely to be experienced as personal failures and more likely to be understood as meaningful signals. That understanding often changes not only how people feel, but how they engage in their own healing.

Coming Next In This Series:

In Part II, we’ll examine how these patterns often occur within adolescence, a period of rapid brain, metabolic, and hormonal development. We’ll explore how SSRIs and hormonal contraceptives are frequently prescribed to teens navigating normal developmental changes—often without thorough evaluation of nutrient status, sleep quality, blood sugar regulation, or overall metabolic health. We’ll also consider how altering neurotransmitter and hormone signaling during these critical windows may have downstream effects on mental, metabolic, and reproductive health later in life.

To learn more about this subject, join FAIR and Dr. Kendra Kautz next week:

We welcome you to share your thoughts on this piece in the comments below. Click here to view our comment section moderation policy.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Fair For All or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diverse range of voices and to encouraging compassionate, good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

I'm a retired psychotherapist. I always urged my clients to get bloodwork done, and several came back with results indicating that their symptoms were due to very low vitamin D or thyroid. In another case with a couple having issues around painful sex, I urged the woman to see a specialist, and she came back with a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Imagine if I had instead worked with the couple on relationship issues!

This shift toward treating anxiey as a signal rather than a pathology is huge. I've seen family members get stuck in that loop where meds mask symptoms but never adress the underlying metabolic or hormonal drivers. The case with the postpartum mom really stuck out to me becuse it showed how normal physological depletion gets mislabeled as just "postpartum blues."