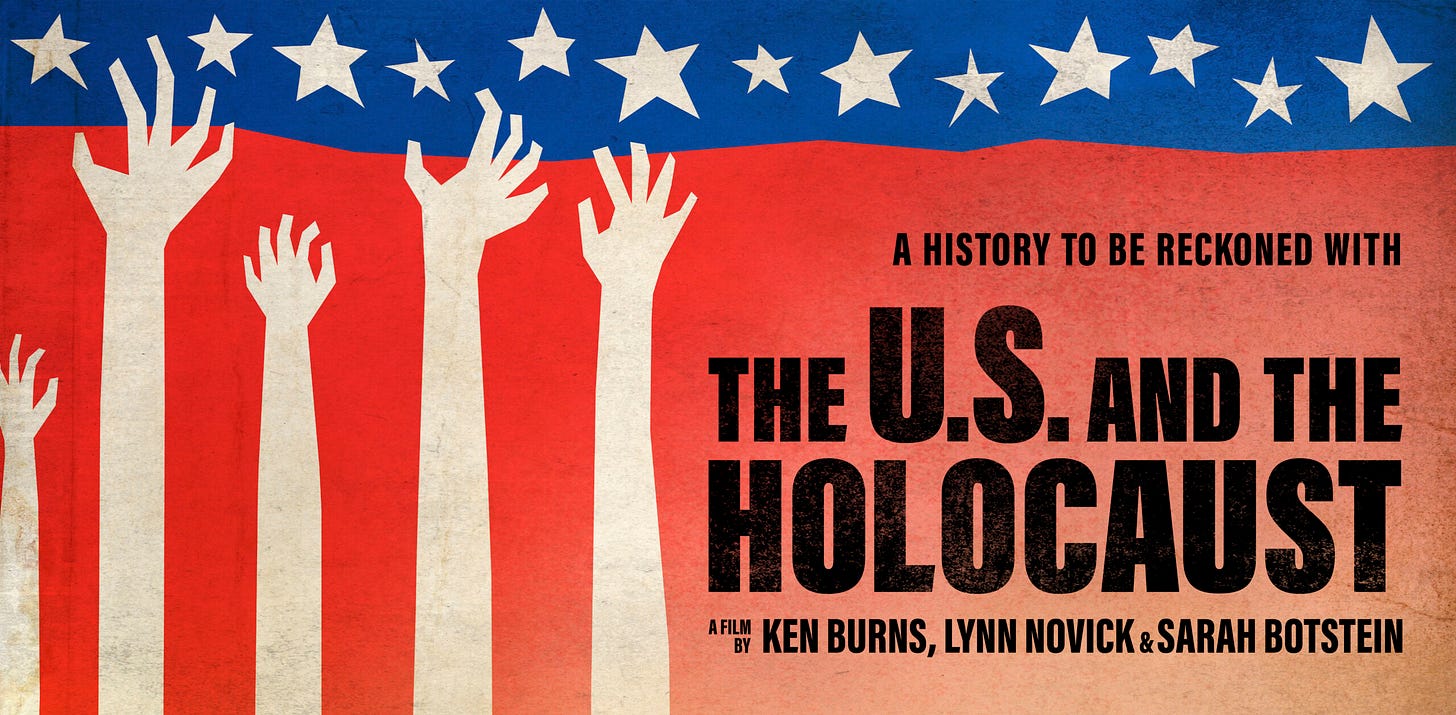

Ken Burns’ three-part documentary on PBS, The U.S. and the Holocaust, provides a nuanced look at the rise of Nazism in Germany and how the United States responded to it. The film gives viewers a window into the immensely difficult decisions that had to be made by American leaders during this period, as well as first-hand accounts of individuals and families dealing with the new changes in Europe. For example: Should President Franklin D. Roosevelt have responded more forcefully to Adolf Hitler’s mistreatment of the Jewish people in the early to mid 1930s, and risked provoking Hitler to abuse them further? Or should the United States not have responded at all, which could have been interpreted by the Nazis and the rest of the world as tacit approval for Hitler’s actions, but may have given more time for peacemaking before a world war? The documentary also evokes more existential questions: How do we determine which outsiders will fit within our tribe? What does it take for an “outsider” to become an “insider?” Is it always wrong to be cautious of “outsiders?” No answer seemed easy.

At the root of Burns’ film is the idea that all humans wish to be valued, and yet all humans struggle in recognizing the humanity of their neighbors. An especially powerful moment in the documentary was when General Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the liberated German Buchenwald Camp. Amidst the horrifying sight of hundreds of corpses in various stages of decomposition, Eisenhower declared, “We are told that the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now at least he will know what he is fighting against.''

This quote embodies the general perspective that it seemed Burns wanted us to align with: In order to prevent mistreatment, war, and human rights abuses, we must fight against our enemies and the evils they carry out. This idea felt even more hammered in during the documentary’s final few minutes. As the music swelled with an uneasy and ominous tone, the screen flashed through images of past horrors and gradually began to take us progressively into the modern day. We were shown magazine covers featuring anti-immigrant rhetoric; pictures of anti-Muslim graffiti; a brief news clip of Charleston mass-shooter along with the headline “Hatred towards blacks, Hispanics, Jews”; a protest sign that read “Build the wall, nice and tall” along with audio of Donald Trump saying “My first hour in office, those people are gone”; a Fox News clip about replacement theory; videos and images from the Charlottesville protest and riot and the shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue; and finally, footage from the January 6th insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

While of course we must oppose all the hateful beliefs which Burns underscores in his closing montage, I found this ending to an otherwise nuanced documentary to be a missed opportunity. Given the complexity of the the film’s treatment of how the United States responded to the Holocaust, I would have expected Burns to cover America’s contemporary issues in a similarly thoughtful way. Instead, this closing montage misleads the viewer to think that one side of the political spectrum is in favor of these hateful beliefs, while the other side is defined by their virtuous fight against them.

A huge part of the civil rights movement’s success came from its nonviolent and compassionate resistance to hatred and injustice, and its insistence that through moral courage and leading by example, individuals could be taught to recognize and overcome their capacity for hatred. When we can no longer recognize the humanity of others—including even those who hate us—we quickly fall into the trap of hating them back. We dehumanize and vilify them by convincing ourselves that some people, through their own actions or beliefs, can be stripped of their inherent worth as human beings.

The missed opportunity in The U.S. and the Holocaust is that it seems to take Eisenhower’s statement at face value. Rather than engage in the complexity and nuance required to discover what was being—and should be—fought for, the documentary decided to end by highlighting once again what—and who—should be fought against. The focus was on human evil rather than humanity; vanquishing monsters rather than converting or preventing them; getting rid of problems instead of focusing on solutions.

In the days, months, and years ahead, our greatest challenge as a nation will be whether we can rise to the task of seeing outsiders—those who think, believe, and behave differently than we do—as reflections of ourselves, and to refuse to define ourselves as simply being in opposition to them. While Burns’ documentary was clearly intended to warn us of what could happen if we divide and dehumanize one another, it fell into that very trap by appearing to frame those who hold beliefs and ideas we find deplorable as somehow inherently deplorable themselves, as enemies to defeat.

There were plenty of moments of unity and uplift throughout the documentary, of countries and individuals coming to aid, and in the forming of families, new and old, despite disaster and devastation. I found those moments inspiring, despite the horrors the documentary was bringing to light. It’s a shame that Burns decided to close with an emphasis on division instead of that sense of unity and hope. It’s certainly a harder fight, and much more difficult to rally around what we’re for rather than what we’re against. But if we are to prevent future Holocausts from happening, we must start seeing each other as more than just people we oppose. It’s not enough to remember and warn of all the bad ideas and behaviors we are fighting against. We must be clear in what—and who—we’re fighting for.

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism or its employees.

In keeping with our mission to promote a common culture of fairness, understanding, and humanity, we are committed to including a diversity of voices and encouraging compassionate and good-faith discourse.

We are actively seeking other perspectives on this topic and others. If you’d like to join the conversation, please send drafts to submissions@fairforall.org.

Join the FAIR Community

Become a FAIR volunteer or join a FAIR chapter.

Join a Welcome to FAIR Zoom information session to learn more about our mission, or watch a previously recorded session.

Take the Pro-Human Pledge to help promote a common culture based on fairness, understanding, and humanity.

Join the FAIR Community to connect and share information with other members.

Share your reviews and incident reports on our FAIR Transparency website.

Read Substack newsletters by members of FAIR’s Board of Advisors

Common Sense – Bari Weiss

The Truth Fairy – Abigail Shrier

Skeptic – Michael Shermer

Habits of a Free Mind – Pamela Paresky

Journal of Free Black Thought – Erec Smith et al.

INQUIRE – Zaid Jilani

Beyond Woke – Peter Boghossian

The Glenn Show – Glenn Loury

It Bears Mentioning – John McWhorter

The Weekly Dish – Andrew Sullivan

Notes of an Omni-American – Thomas Chatterton-Williams

Culture War Musings - Lisa Bildy

The Wisdom of Crowds Newsletter - Shadi Hamid

Let's Get BOARD! - Jonathan Kay

Broadview - Lisa Selin Davis

I disagree with this assertion: "if we are to prevent future Holocausts from happening, we must start seeing each other as more than just people we oppose". What we must start doing is refusing to accept the obliteration of the distinction between two events that have nothing to do with each other. The Holocaust is not "like" any of the events portrayed in the montage at the end the film. It was sui generis. To draw a comparison of it to anything else diminishes the crime and soils the memory of those who perished.

I think it's important to remember that Ken Burns is first and foremost a film maker. His grasp of history has always been somewhat shaky, and underscores how frequently journalists and filmmakers are confused with historians in the public mind. Burns seems especially unaware of the dangers of both race essentialism (and identity essentialism, which is gaining momentum these days) and othering, both of which played directly into what the Nazis were able to do and the relative ease with which they were able to do it. When people are defined only by labels (based on race or self-proclaimed identity) it becomes very easy to marginalize and dehumanize those outside a particular label, and equally easy to blame every problem under the sun on those same labeled groups. Burns of course also chose to ignore events that didn't fit into his particular political message, which diminishes his claim to be any sort of historian. We should be wary of anyone claiming to be "on the right side of history"...history has no sides. Only those spinning it have sides.